Abstract

As more men attempt vegan or vegetarian (collectively referred to as veg*) lifestyles, the historic link between meat and masculinity has become more pronounced. Women tend to gravitate toward several traits associated with veg* diets (e.g., compassion and health). However, the emasculation associated with these diets may also repel them. This project utilized a mixed-methods analysis. It uses survey data (N = 28) and in-depth, one-on-one interviews with six women who have dated veg* men. I recruited subjects using convenience sampling from personal social networks and veg* conferences. The present study explores whether heterosexual and bisexual women are attracted to the masculinity of vegan and vegetarian men more than their omnivore counterparts. Findings indicate that most women tended to view veg* diets as a masculine strength and an indicator of kindness, a concept I dub strong-kindness. With strong-kindness, this version of ideal masculinity moves a little more into the feminine side while still remaining firmly within the masculine part of the binary. Utilizing aspects of veg* lifestyles might improve the health of all as well as the environment. Removing the stigma associated with these lifestyles may help improve the lives of all individuals regardless of gender identity.

Introduction

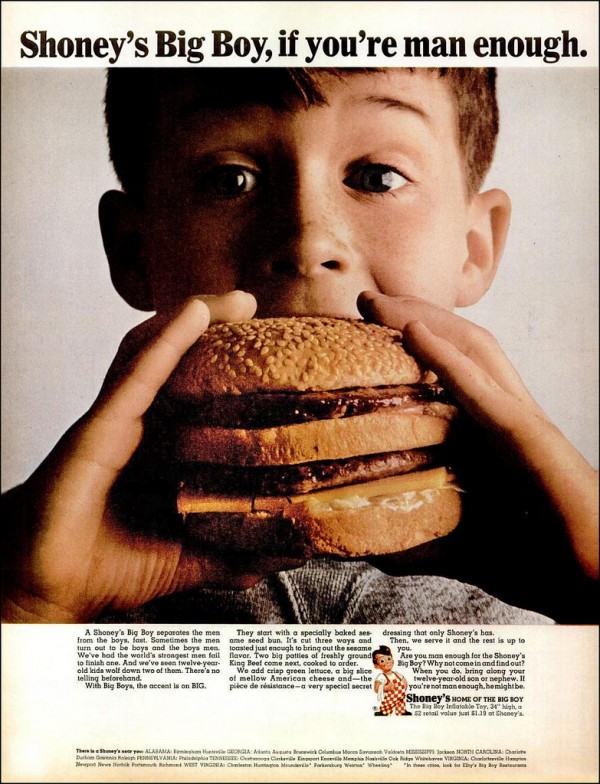

There is no doubt a connection between the consumption of meat and masculinity. It appears in books, articles, and as a trope in the media: from the rugged cowboy figure killing and eating his own game to recent ads depicting men dismissing “tofu” for a double Whopper (Sobal 2006). And this phenomenon is not limited to the Western hemisphere. It exists in places from Argentina to Japan (DeLessio-Parson 2017; Morioka 2013).

Many call on biology and human evolution to explain men’s supposed natural affliction for meat. Researchers draw upon men’s stronger physique and reference the adaptations humans have gone under to process meat better than our primate ancestors. All this is to argue that nature has designed men to eat meat (Leroy and Praet 2015; such as discussed by Zink and Lieberman 2016). By extension, some argue that women desire these masculine traits as well (Sell, Lukazsweski, and Townsley 2017).

More and more men recently, however, are beginning to adopt a vegan or vegetarian lifestyle (Mycek 2018). This way of life goes against these supposed social and biological norms. There are multiple studies that examine veg* men’s masculinity. Members of all diets tend to view veg* men as more righteous. But they still consider them less masculine than their carnivorous counterparts for choosing to forego meat (Ruby and Heine 2011; Thomas 2015). Interviews with meat-eating men reveal that an often cited explanation for consuming meat is to maintain masculinity (Newcombe et al. 2012). Talking with veg* men also uncover the masculine ways in which they discuss their veg* diets to conserve their masculinity (Mycek 2018).

There are existing discussions on the role of meat in heterosexual, romantic relationships where either both partners or the man is omnivorous. But few have explored when the roles are reversed (Sobal 2006). This has lead to my current research which asks whether heterosexual and bisexual women are attracted to vegan and vegetarian men more than their omnivore counterparts.

Literature Review

Masculinities

Essentialist

Groundbreaking masculinities scholar R.W. Connell summarizes essentialist masculinity with such traits as “risk-taking, responsibility, irresponsibility, aggression” and general toughness (2005). However, she also notes that a defining aspect of essentialist masculinity is its “arbitrary” nature (Connell 2005). There is a general, related framework of masculinity that individuals can construct from the above traits. But there is not a reliable source from which one can derive all these traits. In that sense, essentialist masculinity, supposedly rooted in biology, is rather amorphous.

For veg* diets, this manifests itself by drawing on the supposed biological necessity of humans, and men, in particular, to eat meat. There is evidence that suggests that meat was an indispensable aspect of the diets of humans and proto-humans. Moreover, men were instrumental in providing it for their communities (Kaplan et al. 2000; Zink and Lieberman 2016). Many Americans since the 19th century have deemed cultures with more plant-based diets as more effeminate than “meat-eating Englishmen” with this reasoning (Gambert and Linné 2018). The implication is that for strength and masculinity, one has to eat meat of the supposedly natural amount to which the white, American male adheres.

Normative

Some attempt to circumvent the unstable foundations of essentialist masculinity by relying on normative masculinity. This concept dictates what men should be and usually relies on essentialist concepts. It prescribes that although men are not entirely essentialist, it insists they should aspire to be (Connell 2005).

This usually takes the form of the Protein Myth, concern around protein intake for veg* people. This is the falsified myth that plants cannot provide the necessary amount and types of protein required to remain healthy (Woodvine 2009). This is somewhat more gender neutral than some other concepts tied to the meat and masculinity complex. However, the gender normative viewpoint that men should be hunters because of their physiological adaptations necessitates that they need a source of protein for stamina and maintaining muscle. The Protein Myth aids in this regard when it contends that plant sources are inadequate to provide, in reality, an overabundance of protein. This myth keeps veg* curious men from trying out a more plant-based lifestyle due to the supposed protein requirements hardwired into their male DNA.

Semiotic

Finally, there is semiotic masculinity, defining masculinity by which it is not: femininity. As a framework of analysis, has benefits over the former two methods. It does not intend to assume and reinforce essentialist masculinities. Rather, it observes things as they are and categorizes them based on the gender of their original actor (Connell 2005).

More recently, Kristen Barber utilized a framework in her work on the men’s grooming industry she dubs the “Passive Voice.” In this work, she studies the concept of masculinity indirectly. She asks women in the industry how they relate to the concept. She also inquires into how they think of the concept themselves (Barber 2019). This makes sense for the context; much of the interactions in these spaces are with female groomers. However, it applies to the current research as well. I develop a conception of masculinity from the words of women. These women use implicit and explicit versions of semiotic masculinity during our discussions.

Plant-based lifestyles are often associated with feminine-coded dieting. Women are more aware of dieting and healthy foods. These foods tend to be more plant-based (Arganini et al. 2012). Thus, the public relates plant-based lifestyles and foods with femininity. By extension, they connect masculine eating to meat-heavy meals with little regard for health. Cultural products like Seinfeld’s “The Wink” succinctly encapsulate these concepts. While on a date with a woman at a steakhouse, the main character, Jerry, finds its offerings too rich for his liking. He opts for a salad to the disdain of his date. This decision is later admonished by his female confidant Elaine and the date as well. In essence, choosing the light, vegetable-based salad serves to emasculate Jerry (Ackerman 1995).

Performative

Judith Butler’s conception of sex and gender relates to semiotic masculinity in that it is not based on anything concrete. In fact, Butler argues that both sex and gender are a social constructed. Thus, there are no static versions of them. The only way these concepts manifest themselves is through the performance of gender. Gender only exists when it is being performed and thus is always in flux and open to change (Butler 1990).

Precarious Manhood

Precarious Manhood is a concept that has its basis in Butler’s performative theory. It states that manhood has to be constantly earned by the approval of others. Thus, men harbor anxiety over having to continually prove themselves in this manner (Vandello and Bosson 2013).

For men, eating meat bolsters Precarious Manhood multiple times a day. However, where this manhood is especially apparent is when men cook. Cooking for men usually takes the form of grilling in social settings. They maintain their masculine status by grilling and eating meat. But they are also performing these acts in front of an audience. Society views women cooking, conversely, as part of female nature. Thus, women’s countless more hours cooking in the kitchen are not as recognized compared to when a man cooks on special occasions.

Works like Hollows’ discuss this phenomenon (2003). Celebrity chef Jamie Oliver’s show The Naked Chef tends to reconstruct cooking as a masculine, leisure activity. This interpretation differentiates from the necessary, laborious cooking that many women have to thanklessly endure on a daily basis. Shows such as these glorify and masculinize cooking in the public light, assuaging Precarious Manhood in the process (Hollows 2003).

Hegemonic

Connell defines hegemonic masculinity as practices and structures that ensure the patriarchy. It may not always be violent. But hegemonic masculinity is often connected to types of institutional power. It has the ability to dictate culture and behavior on a broad scale (Connell 2017).

For meat, this takes the form of those high up in the meat marketing, processing, and development fields. The Meat Industry Hall of Fame is an organization that bestows honors upon those with significant contributions to the meat industry. Only three of the 92 people recognized are women (2019a).

But it also takes more unexpected forms. Notably, influential political leaders often have financial and symbolic ties to meat. Ted Cruz, pork product in hand, advertised for the National Pork Board at the Iowa State Fair while debating a woman on LGBT rights. His commanding stance at the grill heightened his dismissive, dominant attitude toward the debate (CBS News 2015). And according to Politico, the board takes unfairly from hog farmers. The money goes to Super-Pac-esque groups that benefit politicians (Vinik 2019).

Furthermore, President Trump twice presented a spread of meat-laden fast-food-fare to champion football teams. He noted that these men “aren’t into salads” and would want this “great American food” instead" (Boren and Bieler 2019; Klein 2019). The president presenting this feast of processed meats reinforces this hegemony at a federal level by itself. However, he also does this in front of men playing an extremely masculine sport in America. This incident supports Trump’s Precarious Masculinity. It augments the symbolic masculine power of the meat as well.

Analysis

The analysis in this work draws on all the masculinities presented above. But it will mostly rely on the social constructions of masculinity, largely focusing on performative masculinity.

Men Foregoing Meat

Men who choose not to consume meat risk losing some of their masculine status in the process. Thomas (2015) demonstrated this impact in her study in which participants rated profiles. Some of these profiles were of individuals following veg* lifestyles. She found that it was not always the veg* diet itself that caused emasculation. Rather, it is the choice to follow it. This rejection aligns with masculinities portrayed in works like Guyland (Kimmel 2008). Men who do not look masculine can perform masculinity (e.g., rape culture, sports) so that male peers may accept them (Kimmel 2008). Meat is yet another way to perform this same type of masculinity.

Ruby and Heine’s (2011) study was similar in that participants also rated profiles of vegetarians and omnivores. This study was unique, however, in that it controlled for the healthiness of the diets presented. Subjects ranked the vegetarian profiles as “more virtuous.” But they were still perceived as less masculine than their omnivorous counterparts. A survey distributed to undergraduates at a Kentucky university by Rothgerber (2012) found that men justified eating animals in a direct way. Women tended to try to dissociate meat from its animal origins. Men tended to vindicate meat consumption as a way to maintain their masculinity (Rothgerber 2012). Brady and Ventresca (2014) analyzed media attention after prominent NFL running back Arian Foster announced his conversion to veganism. They explored the extent to which the media reinforced the link between football, hegemonic masculinity, and the consumption of meat (Brady and Ventresca 2014).

One of the most recent entrants into the literature was conducted by Mycek (2018). She conducted in-depth interviews with veg* men about how they aligned their masculinity with their emasculating diet. Many of the subjects justified their diets using logic and science, even when their reasoning is usually coded as emotional (e.g., concern for the treatment of animals). This masculine rationality, the author argues, contrasts with the feminine-coded emotional reasoning that often accompanies explanations for a veg* diet. For example, a woman might cite an emotional connection with animals as her reason for being veg*. Instead, a man might cite research that proves animals feel pain on an equal level to humans.

Meat as a Symbol

Meat as a symbol of masculinity has chiefly arisen from sociobiological musings. As discussed earlier, it has largely stemmed from essentialist and normative forms of masculinity. These versions have propagated a socially-constructed caveman mythos. This narrative argues that because men were the primary providers of meat and calories for themselves and their communities, it was and is necessary for them to consume it to maintain an adequate amount of strength (Kaplan et al. 2000; Zink and Lieberman 2016). Of course, this rarely persists in contemporary society where only a select few in most Western societies hunt to survive. Precarious Manhood has aggravated this essentialist form of masculinity into a social phenomenon that confirms the link between meat and masculinity.

Academic literature on this topic elucidates the mechanisms at work behind this connection. One of the original and most seminal works on the subject is Carol J. Adams’ The Sexual Politics of Meat, published in 1990. Adams asserts that Western culture dictates “men need meat,” that it is a symbol of masculinity and strength, and that eschewing meat is a marker of femininity (Adams 2010). As masculinity studies have grown over the past few decades, accepted definitions of masculinity have lined up with Adams’ original assessment. Since the original publishing, other studies have confirmed Adams’ observations. Sobal (2006), for instance, argued that the ways men eat and provide meat symbolize strength, health, and wealth depending on the situation.

Metrosexuality

Metrosexuality is an intermediary between more traditional masculinities and the soyboys concept discussed below. This masculinity still emphasizes heterosexual desire. However, it also adds narcissistic tendencies with the goal of admiration by both men and women. The latter point usually requires men’s participation in feminine-coded behaviors, such as cooking, cleaning, grooming, and healthier diets (Barber 2016; Buerkle 2009; Simpson 2002).

Individuals and corporations invested in maintaining hegemonic forms of masculinity have caught onto this trend. Buerkle (2009) discusses how, in an attempt to snuff out burgeoning metrosexuality, prominent users of meat, like burger chains, advertise their products as masculinity reinforcers for their consumers. There are attempts to reject metrosexual “bluefish from cedar planks” for “burgers from wax-paper wrappers” instead (Buerkle 2009). And, because “fish meat is practically a vegetable,” this feminine symbol is denied in favor of its cow-sourced counterparts (Yang 2011).

Soyboys

Recent discourse about plant-based diets and emasculation has taken the form of the insult “soyboy.” This study is one of the first to analyze the term. Google Trends reports that it became popular in late 2017 (Google 2019). Thus, the history of the term is limited mostly to internet sources, confirmed by Gambert and Linné (2018). Urban Dictionary definitions describe Soyboys as a new way for those on the alt-right to refer to effeminate, feminist, liberal, Nintendo-loving men (2019b). This has started to build upon and replace the alt-right’s historically used cuck, short for cuckold. Beyond its original definition of a man with a wife who cheats, it also refers to a passive man and implies someone with progressive views. This term actually has a presence in established dictionaries (Oxford University Press 2019).

The only academic source discussing the topic I found at the time of this writing is one by Gambert and Linné (2018). They trace the history of soyboy back from an emasculated rice eater stereotype. This prejudice was used as an excuse for colonialism in Asia during the 19th century. Authoritative figures in the West at that time believed that eating animals made one intellectually and physically superior to cultures that had more plant-based diets (Gambert and Linné 2018).

Media portrayals of the term tend to focus on members of the alt-right who consume milk to retaliate against the consumption of emasculating milk alternatives supposedly drunk by soyboys (Hathaway 2017; Hosie 2017). Gambert and Linné suggest these men draw upon the mythos surrounding milk in early-20th century America. For Americans at that time—influenced by large dairy corporations—milk symbolized strength, colonialism, and idealized masculinity (2018). For soyboys, the types of men that the women I interviewed for this project dated, these are the types of values that they rejected. This, therefore, would emasculate them in this context.

Eco-fascism

Another related concept is the connection between sects of white supremacist ideology and veg* diets, stemming from the idea of “Blood and Soil.” This is a Nazi ideology that advocates for conservationism, organic farming, and, often, a veg* diet. These German’s believed sovereignty to their homeland solidifies this culture. These people also link the perceived purity of veg* diets to the purity of the white race (Forchtner and Tominc 2017). In fact, both eyewitness accounts and biomedical evidence suggest that Hitler was mostly vegetarian as well (Nikkhah 2013; P et al. 2018).

Some contemporary followers of this movement have adopted Hitler’s stance by also following a more plant-based lifestyle. One website, aryanism.net, has an entire section lauding veganism (Aryanism 2009). Another article describes how organic farming has become desirable by some members of the German right (McGrane 2013). One study discussed how the content of a vegan, German, Neo-Nazi YouTube cooking show Balaclava Küche (Balaclava Kitchen) intertwined Neo-Nazi ideology into the principles behind veg* diets (Forchtner and Tominc 2017).

Further research between the link between Neo-Nazi and white supremacist ideology, their masculine ideals, and veg* diets is required and is out of the scope of this paper. However, it is interesting to consider how these concepts may start to be more influential as the alt-right continues to gain international traction. The link to prominent male figures in white supremacist circles such as Hitler could generate a new version of plant-based masculinity. This may end up challenging the soyboy concept.

Summary

When most think of the link between meat and masculinity, they either consider essentialist arguments for masculinity or the media’s influence on the concept. However, as presented in this section, there are more versions that tie the two ideas together. There are often subtle ways that meat and masculinity symbiotically interact with one another. As a result, there are harmful ways that this can reflect upon men who decide not to associate with this symbol. In sum, men and women use the masculine symbolism and imagery associated with meat through various types of masculinity to police men’s gender identity.

Heterosexual and Bisexual Female Attraction

Using data from a major online dating website, Hitsch, Hortaçsu, and Ariely (2005) found that women tend to prefer men who are in masculine, health-related lines of work. Women also tend to prefer men who have higher levels of education. A controlled study of speed dating by Fisman et al. (2006) confirmed these results, adding that women also seek physical fitness and financial stability as well. A preferences survey given to countries around the world confirms the results above. This survey confirmed that high social status is desirable too (Shackelford, Schmitt, and Buss 2005).

Americans tend to associate veg* diets with female, attractive, intelligent, middle- and upper-class individuals. This often takes the form of the celebrity in media representation of veg* diets (Mooney and Lorenz 1997; Mycek 2018; Ruby and Heine 2011; Ulaby 2014). The American public tends to perceive veg* men as less attractive than their omnivore counterparts because of the emasculation associated with these diets. Mainstream American media publications such as the New York Times, The Atlantic, and NPR have all reported on this phenomenon (Beck 2018; Brubach 2008; Rothman 2018; Ulaby 2014). This trend is even present in countries around the world, such as Argentina, Australia, China, Finland, Japan, The Netherlands, and Turkey (DeLessio-Parson 2017; Lockie and Collie 1999; Morioka 2013; Nath 2011; Roos, Prättälä, and Koski 2001; Schösler et al. 2015). In particular, Japan has the concept soushouku-kei danshi. This term literally means “grass-eating men” and is called “Herbivore Men” in English. Herbivore Men are undesirable, feminized men who are not aggressive in pursuing romantic relationships and sex, have a more feminine fashion sense, and sometimes eat a less carnivorous diet. The idea became popular in the Japanese media and the Western media as well, to a lesser extent (Charlebois 2013; Chen 2012; Harney 2015; Khan 2016; Lim 2009; Morioka 2013; Neill 2009; Nicolae 2014; Otagaki 2009).

Current Research

Although many discuss the masculinity of veg* men, researchers tend to remain hypothetical. They will rely on rating fictional profiles, for example. It’s only recently, with studies such as Mycek’s (2018), that have started to explore the complexities of living as a veg* man. Nobody has asked women, the primary judge in these situations for heterosexual veg* men, how they view their attractiveness and masculinity. I answer this question with data from the women in romantic relationships with veg* men. This study intends to illuminate what other researchers only suggest. It will attempt to answer whether heterosexual and bisexual women are attracted to vegan and vegetarian men more than meat-eating men.

Methods

Survey

I utilize a multi-methods approach. First, I distributed a survey (provided in Appendix B) via the snowball method. I circulated it at a veg* conference in Los Angeles with instructions to those I distributed to pass along the survey to people they knew who met the criteria. I also utilized my Facebook and Instagram social networks with instructions to recruit peers to take it as well. The ad I used for both in-person and online contexts can be found in the appendix. 31 people responded to the survey from September 2018 to January 2019. I excluded three from the sample because they did not meet the study criteria, resulting in a sample size of 28. I used Google Forms for distribution and analyzed data with Stata/SE 15.1.

I recruited both men and women for the survey part of this analysis. I chose both to draw comparisons between the two genders and expand my network for potential interview subjects. There are a couple of questions at the beginning that screen out anyone who has not been in a relationship with a vegan or vegetarian person for at least a month. I chose a month arbitrarily to make sure that interviewees would have had ample romantic experience with their partner. This would result in richer, detailed, and reliable responses. This did not end up mattering much in the end as the average relationship length was 2.6 years after eliminating one outlier. Furthermore, anyone who identifies as any other gender other than male or female was also eliminated. I am concerned with constructs of masculinity and femininity. Thus, the experience of genderqueer persons would not be applicable to the study. At the end of the survey, I asked basic demographic questions. Space was also provided for women who were interested in being interviewed for the study to leave contact information.

The bulk of the survey measures the gender expression of both the respondent and their ideal partner. I used a variety of methods to measure gender. First, I decided to forego more traditional measures of masculinity and femininity, like the defunct Bem Sex-Role Inventory created in 1974 (Bem 1974; Stenberg 2017). In fact, the only items that significantly correlated with men and women on the BSRI were the terms “masculine” and “feminine.”

Recent research has discovered this method is best as well, such as Kachel, Steffens, and Niedlich’s (2016) work. Their inventory asks about gender-roles, identities, interests, beliefs, and so on using a Likert scale of “Very feminine” to “Very masculine.” Comparing multiple inventories, including Bem’s, Kachel et. al. (2016) found their Traditional Masculinity and Femininity scale to be the most accurate in both implicit and explicit gender reporting. For example, TMF was one of the only scales to distinguish in gender expression between both heterosexual and homosexual women and men. However, some other methods of measuring were also included that also draw on recent research based on dating preferences research cited in the literature review (such as Hitsch et al. [2005] and Fisman et al. [2006]). Finally, I gathered demographic information in the final part of the survey, including age, education, and race. A copy of the survey is in the appendix.

Interview

I conducted six in-depth qualitative interviews with women. Most participants were drawn from the survey sample. A few, however, were found separate from it. All participants had the same screening criteria as the survey respondents. Interviewees were interviewed either in-person or over the phone. All interviewees signed consent forms as well. Interviews averaged approximately an hour long. I recorded both and created transcripts for further analysis. The average age of interviewees is 27 years old, the minimum being 21 and max 35. Three subjects identified as white with one specifying Armenian. Two more identify as Asian while the last identifies as Latina. The sample is half heterosexual and half bisexual. All participants are either middle or upper class, save for one who identified with lower class. All interviewees are also vegan or vegetarian except for one who used to be. This sample, again, follows the typical demographics of veg* studies so far, which primarily consist of middle- to upper-class white women.

I conducted deductive coding on transcripts using NVivo 12. I use a combination of versus and values coding to analyze the interviews. I utilize versus coding because I am analyzing the binary of masculinity and femininity. It was helpful to use this when first going through the texts to have some frame of reference for initial codings. I also employ value coding because my goal is to measure what these women believe about masculinity. After an initial coding, I refined the codes and placed them into categories. The largest one is “Strength” for masculinity and “Emotional” for femininity. I added a third main code, “Strong-Kindness,” later that is the crux of the analysis below.

Ethical Concerns

After I reached out to all potential subjects from my survey pool, I destroyed all contact information. I then gave the interviewees pseudonyms. Furthermore, identifying details, like location data and names, and other information as requested by the interviewee were removed from the transcripts. Interview audio is destroyed after transcription. The rest of the data from this project is kept on an external, password-protected 256-bit AES encrypted drive. The only physical data from this research are consent forms. The original is scanned, destroyed, and then stored with the rest of the data on the encrypted drive.

It is important to mention that I myself am vegan and present as male although I did not disclose this information explicitly in my interviews. The possible implications of this are discussed in the “Limitations” section below.

Discussion

After completing the collection phase, I discovered the qualitative part of the research answered the research question most directly. To uncover the interactions between the various variables at work for such a personal topic, such as emasculation, positive veg* qualities, and gender roles, interviewing is the optimal choice. In principle, quantitative methods can approximate the quality of data achieved through qualitative ones, especially on a larger scale. But quantitative methods are not as appropriate in this context due to the small sample size.

However, novel qualitative research such as this can inform future quantitative data collection, like suggested by Pearce (2002). In fact, there is a unique finding from the present survey data discussed further in “Future Research.” Furthermore, the survey data provided a solid foundation for the qualitative findings.

Results

Survey Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 in Appendix A provides detailed descriptive statistics of survey respondents. The sample consists of 15 women and 12 men. The average age is 26 years old. Two-thirds of the sample are heterosexual and a third are bisexual. Three-fourths of respondents are white. There are three Latinos and the rest are either Asian or multiracial. The average survey-taker is a college graduate and has an annual salary of $50,000 to $75,000. 2.6 years is the length of the average relationship (with one outlier excluded). The demographics of these survey-takers align well with extant samples and veg* stereotypes: white, educated, middle-class women.

Veg* Rationale Trifecta

Participants in this study tended to name three categories for reasons they went veg*: environment, ethical, and health. Some also chose more than one. One participant said “I like the way [veganism] makes me feel physically. And I also support animal rights.” Another said she “supported everything: environmentally, health-wise, and also for animals.” Yet another stated that it is “first and foremost environmental reasons, then moral and ethical reasons, and then health reasons.” Zoey is the only one that initially didn’t go veg* for one of these reasons, rather doing it for “convenience.” But she “started looking into animal rights and the environmental effects of vegetarianism later on.”

Writing on veg* diets makes frequent use of these three categories. But no one yet has codified them. This categorization is of interest to those who study diets because it elucidates how people with special diets feel the need to rationalize them to the outside world. There are certain lines of reasoning that people accept more than others. Veg* diets are rare and unusual to most of the population. Thus, vegans, vegetarians, and omnivores sometimes view following a veg* diet for no reason, or even for health (which Kassity explicitly admonished, for example), as an unsatisfying reason for rejecting many cultural norms.

The self-righteousness often attributed to veg* diets also helps explain this attitude (Greenebaum 2012). To dispel this aura, veg* people will use the veg* trifecta in personal terms. They will assert that they are veg* because they feel personally that it’s the right thing to do. This is instead of claiming it’s the right thing to do, thereby establishing some sort of external, universal moral code. Although this is a subtle rhetorical shift, it is in an attempt to deflect any backlash that they may face from percieved self-righteousness (see Greenebaum 2012).

Implicit Veg* Gendering

When asked whether vegan and vegetarian diets are gendered, many women said no. One could not, “give any kind of gender…,” remarking that she “[couldn’t] decide whether it’s feminine or masculine” and “hop[ing] it’s universal.” Another thought that “it’s a pretty gender-neutral thing.” She does not “associate being vegan as being [feminine or masculine].” Another woman also sees veganism as a gender-neutral thing. Finally, one subject “never even thought that was an issue.” All other interviewees viewed the diets as masculine, discussed below. This was likely an attempt to save the masculinity of their men by applying a masculine framework to the veg* lifestyle. In other words, the women who were veg* did not see their diet as masculine.

These results are in line with the data displayed in Table 2. Every category other than “Self-Reported Gender Expression” is rather gender neutral, around a 3 on the scale of 1 to 5. All the men and women who took the survey supposedly act gender neutral. They also desire gender neutrality in their partner.

However, these statements and survey results contradict the rest of these women’s transcripts. It is possible that those who took the survey and the interviewed women aspire to gender neutrality. It could also be that they are uneducated or too disinterested in the topic to have a solid opinion. I claim the former. As detailed below, most women have ideas of masculinity and femininity as they interact with veg* diets.

Strong-Kindness

In general, the women I interviewed for this project saw veg* diets as a masculine strength. They also value and desire more feminine traits from their men as well. The combination of these two traits is a concept I dub strong-kindness.

Justice

Kassity

Kassity is a 35-year-old white, bisexual, “non-monogamous” woman. She grew up and continues to be upper-class. She had been vegan for approximately 7 years at the time of our interview and vegetarian for many years prior. It was an ethical consideration in her youth that grew to include environmental and health concerns. All this culminated into her work as an environmental and vegan activist.

She first met her now-husband via various random encounters, starting approximately 12 years ago. After dating four years, they became married in 2011. At that point, Kassity was vegetarian but interested in becoming vegan. Her husband was an omnivore at the time. But, as Kassity continued and completed her vegan transition, he began to follow suit. At the time of the interview, they had both been vegan together while raising a vegan family for about a year.

Kassity views veganism as a strength, but in more gendered terms. She sees veganism and vegan activism as “stand[ing] up for justice and integrity and honor.” She extends this statement to “real men, real women, [and] real humans.” Kassity goes on to declare that these noble actions are “so sexy to [her].” Most dramatically, when talking about her ideal man, she uses the term “righteous warrior.” This is “…due to reason, someone who’s fighting on behalf of what’s right in the world.”

Her utterances are laden with traditional masculine concepts and imagery. Other than the obvious warrior phrase, she states that she finds “fighting… due to reason” attractive. Established forms of masculinity dictate men should be rational beings. Furthermore, it imposes that they should be aggressive.

Kassity’s ideal behavior differs in what ways these men display their aggression. According to traditional masculinity, men would be harming others with their aggression. This refers more to verbal or emotional violence in the present day. For meat and masculinity, this often manifests in the killing of animals and the environment.

What Kassity finds attractive is the opposite. She likes this traditional masculine aggressiveness, describes it in such masculine terms, and finds it “sexy.” But she likes her partner’s veg* diet as it advocates for non-violence. This combination of aggression for noble causes is a hallmark of justice.

Jade

Jade is a 21-year-old Latino-American student who attends a private Californian university. She identifies as bisexual and had been vegetarian for three years at the time of our interview. Jade grew up on a lower-class ranch in Texas. While discussing farm and meat culture, she mentioned how she became a vegetarian for environmental reasons. This seemed odd to me. When I requested clarification, she remembered she used to believe that farms in general treated and killed animals in the same way that they did on their family farm. Learning about factory farming and the impacts of factory farming led her to question this belief. Soon after, she started transitioning to a vegetarian diet along with her partner at the time.

She met her boyfriend during her senior year of high school. They dated for approximately three years. Jade brought up the idea first in the relationship after taking a class about the science behind environmental issues. She became vegetarian first. But her partner was invested in related conversations. He then followed a couple of months later. She reported him going vegetarian for similar environmental reasons as well as health.

Jade views following a vegetarian diet as an element of a “principled life,” which she values. She explains that it indicates a person’s “amount of strength… and that [they’re] able to live that principled life in [their] actions rather than just in [their] words.” In fact, it was this lack of a principled life that led to the end of her relationship with Jake. This was despite him “being strong in making [the decision to go vegetarian] for himself.” Because Jake brought up the idea first and followed through, Jade believes that it was a strength, especially because she’s aware of the associated emasculation that veg* lifestyles harbor.

The way she explains the “principled life” concept, a synonym for justice, demonstrates the underlying masculine ideals. The desire for others to live according to their values is fairly gender-neutral. But it is the rhetoric Jade uses that implies masculinity. She constantly refers to the “principled life” in her interview. Furthermore, she implies that anything less of holding to your values is not strong. One could argue that Jade insinuates concepts such as complicit masculinity here (Connell 2017). She may be arguing that men who don’t lead “principled lives” are reaping the benefits of the hegemonic masculinity Jade notes she dislikes. In that, she is arguing against a masculine presentation.

But she admires the individuality of veg* diets and adhering to it despite the consequences. He was going against his background, “a man… raised in Texas,” and “against a lot of social norms.” It was something that he “individually wanted.” For her, he was “very strong in making that decision for himself.” Jade professes to like men with “traditionally feminine characteristics.” Indeed, she currently is in a relationship with someone who exhibits those traits (e.g. “outwardly emotional”). But she does not view complicit masculinity as attractive. For men to expected to always live up to their values in every situation is yet another form of unrealistic strength standards imposed on men.

Overview

These women view the values and politics associated with veg* diets as an attractive quality in a man. Some of these values transgress traditional masculinity. For example, concern for animal welfare is a feminine-coded concept because of its basis in emotion. These men may also have “feelings in [their] politics,” a very non-masculine trait.

However, these women often save the masculinity of their partner. Sometimes, it is with rhetoric. This takes a melodramatic form with Kassity’s use of the “righteous warrior.” But it is most often in describing their strive towards justice as a strength. It usually takes the form of always “not being scared” of living out one’s values despite the context or circumstances. This pressure for men to be strong and to always hold to these justice-oriented values is indicative of the traditional masculine expectation to be unwavering in any situation.

When contrasting these experiences with one of the non-veg* interviewees, some differences emerge. Mai, for example, was wary of her vegan activist boyfriend’s “militant veganism.” His extreme stance contributed to her leaving the lifestyle herself. This woman did not put as strong of an emphasis on justice as other participants. Thus, she felt more uncomfortable in the relationship than did the other women who gave praise for their partner’s justice-oriented values and actions.

Strong Mind

Mai

Mai is a 22-year-old, Asian, heterosexual woman who works in the film industry. She became vegan due to “peer pressure” from her boyfriend at the time. He became vegan from reading a book on the subject after the start of their relationship. She had some investment in the issues he advocated for: environmental, health, and ethical issues. But she mostly went and remained vegan to appease him.

Her partner’s interest in veganism and his open-mindedness enamored her. She also cited her own curiosity and open-mindedness as personal reasons for starting the transition. Her relationship with meat was rather unique. She had a strong “urge to eat” meat from the beginning of her vegan escapade. In fact, at times she would say, “‘Hey, I’ll do the dishes’ and then [eat] the pieces of fat that my parents had thrown… I was like, ‘…it’s not going to be any different if it goes in the trash or if it goes in my body.’” All this was to hide from those around her that she was eating meat.

Mai desires someone who is “60% logic, 40% emotion” to balance out her “very emotional” personality. She also “desire[s] stability” in her partner as well as a “strong mind.” She defines this state as when “obstacles won’t affect you” with a “motivation and positivity towards life.” Despite the baggage from this relationship, she still admires the “cool lifestyle [veganism] where your willpower is practiced everyday…”

Mai emphasizes the strength aspect of strong-kindness in her interview. It could be that Mai’s case is unique because of her self-described extremely emotional personality. But the effect is still the same for prospective partners: the expectation to have this unrealistic “strong mind” and unwavering stability.

Nare

Nare is an Armenian-American, 28-year-old, heterosexual woman. Before becoming vegan, she had been a vegetarian for about six years. Her reasoning for being so was for health reasons and animal rights. She had never enjoyed eating meat and found it “depressing.”

She met her boyfriend while working on set in similar departments at a wrap party. He was vegetarian at the time, transitioning to veganism. Despite his likeness towards meat, he was veg* for empathy towards animals.

Nare values “an ability to staying level-headed and rational and not very emotional…” However, she still admired and found necessary the times where her boyfriend “would get really upset sometimes at… the things that matter… he would just need some time for himself… to write about it in his journal… he would get really distraught and empathetic with that event.”

Part of Nare’s rationale for her veg* diet is emotional. But the first reason for her was her health. This topic tends to be more logical than the other points of the Veg* Trifecta (discussed below). Health often incorporates emotional well-being as a part of its definition. However, it is more out of self-interest and the reasoning is more associated with men (e.g., Mycek 2018). Men can back health rationale up with science and statistics. Thus, they can avoid the ethical, more feminine considerations tied to veg* diets.ß

In essence, Nare is on the rational side of things. Yet, she still is able to reconcile with the times when her boyfriend “would get really upset.” The issues he tended to get upset over were noble in nature, “the things that matter,” such as a “shooting.” She leaves personal emotional deliberation out of her assessment. Nare ascribes the strong mind concept to her partner by implying her ideal men would only become emotional over meaningful items that deserve it; to her, anything else would be indicative of weakness. Furthermore, she describes his electronic rigging job as masculine, a says that she believes he is a still a masculine person because of it. Therefore, she saves his masculinity while still applauding the emotion behind the issues that she cares about.

Zoey

Zoey is a white, upper-middle class student who attends a university in California. She tried out veganism approximately four years ago out of convenience. She “got more into politics” her sophomore year. Now, her veganism is more informed by animal rights and environmental issues.

Her boyfriend she started dating at the time also happened to be vegan. She describes him as “anarcho-communist” and a “punk vegan.” He believed that rejecting animal products was rejecting capitalism. This combined with his love for animals.

Zoey would “get looks” with her boyfriend sporting “spiked hair” and “tats” which “didn’t bother him at all.” She “admired that quality of not being scared, of being yourself.” Furthermore, she praised that “he had a lot of feelings in his politics and for the pain and suffering that he saw.”

Being true to one’s self is a trait desirable for any gender. However, Zoey crosses the line into unrealistic expectations for men by expressing how it appealed to her that opposition “didn’t bother him at all.” Resistance affects everyone. Men especially are expected to be solid, unwavering rocks in relationships (Fisman et al. 2006; Hitsch, Alı Hortaçsu, and Ariely 2010; Shackelford et al. 2005). This combines with her approval of the “feelings in his politics” to produce the strong-kindness concept. Her boyfriend should not show much emotion, especially for personal matters. But she still desires an emotional basis for his “politics.”

Overview

Other participants communicated similar desires in their interviews. One liked that her partner went “against a lot of social norms,” and that it was something that he “individually wanted.” He was “very strong in making that decision [to go vegan] for himself.”

The types of qualities these women present are not inherently negative. Rather, it are these women’s expectations and how they describe them that recall traditional masculine ideals. They expect their partners to always be the rock in their relationship. This assumption can force men into an unnatural and unhealthy stoicism. Furthermore, they desire an individualistic attitude in their ideal men. They like the ability of these men to remain steadfast when going against societal norms despite the shame, insecurity, and other emotional trauma that can happen as a result. Their desires rely on traditional tenants of emotional and mental strength ascribed to men.

Discussion

One of the most salient questions to arise out of this research is whether the results are generalizable to romantic relationships or if they only apply to veg* women. The fact that only two women in my sample were not veg* at some point advances this concern.

The results are at least generalizable to veg*, liberal, middle-class women. Beyond that, it’s hard to state broader implications. Most extant research bases itself around these groups, including Mycek’s (2018) study in which its sample comprised of white, middle-class men.

It at least may point to the start of a broader societal change. For example, second-wave feminism focused only on white, middle-class women. Intersectional feminism came along to address its shortcomings.

These women expect their ideal man to remain within the gender binary. But their expectations are still shifted slightly to the feminine side. Non-white, non-middle class will be slower to make this shift. For example, lower-classes tend to buy low-cost meat and meat products to fill bellies. Buying meat products is also a signature of faux-status. It harkens back to the days when meat was more of a luxury for the general population (Chan and Zlatevska 2019).

Conclusion

Limitations

It is important to disclose that I myself am vegan and present as male. I did not inform participants that I am vegan during interviews. Some may have suspected that I am due to my knowledge of veg* issues and concepts. A couple participants happen to know beforehand that I was vegan. The fact that I am vegan and appear male could have implicitly or explicitly affected how they answered my questions. These women seemed candid. But there might have been points when they did not want to hurt my feelings. Or they might have felt uncomfortable talking to a man about some issues.

The sample recruited for this project is more representative than other studies on veg* diets. There were Latina and Asian subjects depicted and a lower-class-raised individual as well. Furthermore, there are interviewees from various parts of the United States. There is also one who grew up outside America.

However, the majority of survey respondents and interviewees came from white and middle- to upper-class backgrounds. This reflects the current demographics of American vegans and vegetarians (Millum 2018). But it would still be beneficial for the research to include as diverse a cohort as possible.

One of the most tenuous aspects of this study is the gender measures in the survey. I made an effort to consider the history of these measures and use multiple, recent versions for the survey. But one could still make an argument against the particular way I wrote the questions. They could even contest the inclusion of these questions at all. Some may point to the rather gender-neutral results as proof that these methods do not work.

For this reason and others, future researchers should seek a larger sample. For the purposes of an undergraduate project, the sample size is adequate. But to achieve greater representation and reliability, more interviews should be conducted. The survey suffers the most from this. At the time of this writing, there are sub-thirty respondents. With more time and resources, it may be possible to, for example, utilize a survey panel to get a representative picture of the American veg* population.

Future Research

One of the unintended findings of my research was the link between sexuality and veg* diets. Table 1 reports that a full third of my sample identified as bisexual. Only about 3.5% of Americans, however, identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (Gates 2011). I suspect that the reason for this disproportionality is due to the correlation between LGBT politics and the veg* politics. Both tend to lean liberal (Reinhart 2019). There is likely a coincidental correlation rather than a biological or sociobiological cause. It would be difficult to test this and it is out of the scope of the current research. It would require finding heterosexuals and bisexuals and measuring their politics as a control.

Another option for future research is to do the same type of project while reversing the genders. In other words, men in relationships with veg* women would be asked how they view their partner’s femininity. This research would serve to clarify aspects of masculinity and femininity like the current project. But this new research would center on constructions of femininity rather than masculinity. It would be an attempt to answer the inverse question of whether the femininity associated with veg* diets makes veg* women more attractive to heterosexual and bisexual vegan men.

Works Cited

Ackerman, Andy, ed. 1995. The Wink. Seinfeld.

Adams, Carol J. 2010. The Sexual Politics of Meat (20th Anniversary Edition). New York, London: Continuum.

Arganini, Claudia, Anna Saba, Raffaella Comitato, Fabio Virgili, and Aida Turrini. 2012. “Gender Differences in Food Choice and Dietary Intake in Modern Western Societies.” Pp. 83–102 in Public Health – Social and Behavioral Health, edited by J. Maddock. Public health-social and behavioral health. Retrieved (https://www.intechopen.com/books/public-health-social-and-behavioral-health/gender-differences-in-food-choice-and-dietary-intake-in-modern-western-societies).

2009. “Veganism.” Aryanism. Retrieved May 2, 2019 (http://aryanism.net/culture/veganism/).

Barber, Kristen. 2016. Styling Masculinity: Gender, Class, and Inequality in the Men’s Grooming Industry. 1st ed. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Barber, Kristen. 2019. “Styling Masculinity: Gender, Class, and Inequality in the Men’s Grooming Industry, by Kristen Barber (Rutgers University Press, 2016).” Pacific Sociological Association Annual Conference 2019 1:30.

Beck, Julie. 2018. “The Sad Ballad of Salad.” The Atlantic. Retrieved September 16, 2018 (theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/07/the-sad-ballad-of-salad/493274/).

Bem, Sandra L. 1974. “The Measurement of Psychological Androgyny.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42(3):155–62.

Boren, Cindy and Des Bieler. 2019. “‘We Have Everything That I Like’: Trump Serves Fast-Food Feast for Clemson’s White House Visit.” Washington Post. Retrieved April 26, 2019 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2019/01/14/clemson-tigers-visit-white-house-meet-with-trump/?utm_term=.fa40de62da8c).

Brady, Jennifer and Matthew Ventresca. 2014. “‘Officially a Vegan Now.’” Food and Foodways 22(4):300–321.

Brubach, Holly. 2008. “Real Men Eat Meat.” New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018 (https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/09/style/tmagazine/09brubach.html).

Buerkle, C W. 2009. “Metrosexuality Can Stuff It.” Text and Performance Quarterly 29(1):77–93.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble. 1st ed. New York: Routledge.

CBS News. 2015. Ellen Page Confronts Ted Cruz Over LGBT Rights. Des Moines, Iowa. Retrieved May 6, 2019 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iu1lsw3_Kfo).

Chan, Eugene Y. and Natalina Zlatevska. 2019. “Jerkies, Tacos, and Burgers: Subjective Socioeconomic Status and Meat Preference.” Appetite 132:257–66.

Charlebois, Justin. 2013. “Herbivore Masculinity as an Oppositional Form of Masculinity.” Culture, Society and Masculinities 5(1):89–104.

Chen, Steven. 2012. “The Rise of (Soushokukei Danshi) Masculinity and Consumption in Contemporary Japan.” Pp. 283–308 in Gender, Culture, and Consumer Behavior, edited by C. C. Otnes and L. T. Zayer. New York: Gender, Culture, and Consumer Behavior.

Connell, Raewyn. 2005. Masculinities. Polity Press.

Connell, Raewyn. 2017. “Gender Relations.” Pp. 53–75 in Gender, Patterns in gender.

DeLessio-Parson, Anne. 2017. “Doing Vegetarianism to Destabilize the Meat-Masculinity Nexus in La Plata, Argentina.” Gender, Place & Culture 24(12):1729–48.

Fisman, Raymond, Sheena S. Iyengar, Emir Kamenica, and Itamar Simonson. 2006. “Gender Differences in Mate Selection.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 673–97.

Forchtner, Bernhard and Ana Tominc. 2017. “Kalashnikov and Cooking-Spoon: Neo-Nazism, Veganism and a Lifestyle Cooking Show on YouTube.” Food, Culture & Society 20(3):415–41.

Gambert, Iselin and Tobias Linné. 2018. “From Rice Eaters to Soy Boys: Race, Gender, and Tropes of ‘Plant Food Masculinity.’” Animal Studies Journal 7(2):129–79.

Gates, Gary J. 2011. How Many People Are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender? Los Angeles, California: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law.

Google. 2019. “Google Trends. ‘soyboy + soy boy,’” April (https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&geo=US&q=soyboy,soy boy).

Greenebaum, Jessica B. 2012. “Managing Impressions.” Humanity & Society 36(4):309–25.

Harney, Alexander. 2015. “The Herbivore’s Dilemma.” Slate. Retrieved April 7, 2018 (http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/foreigners/2009/06/the_herbivores_dilemma.html).

Hathaway, Jay. 2017. “‘Soy Boys’ Is the Far-Right’s Newest Favorite Insult.” The Daily Dot. Retrieved April 24, 2019 (https://www.dailydot.com/unclick/soy-boy-alt-right-insult).

Hitsch, Günter J., Ali Hortaçsu, and Dan Ariely. 2005. “What Makes You Click: an Empirical Analysis of Online Dating.” Pp. 1–51 in, vol. 207. Cambridge, Massachussetts, Chicago, Illinois.

Hitsch, Günter J., Ali Hortaçsu, and Dan Ariely. 2010. “Matching and Sorting in Online Dating.” American Economic Review 100(1):130–63.

Hollows, Joanne. 2003. “Oliver’s Twist.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 6:229–48.

Hosie, Rachel. 2017. “Soy Boy: What Is This New Online Insult Used by the Far Right?” The Independent. Retrieved April 21, 2019 (http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/soy-boy-insult-what-is-definition-far-right-men-masculinity-women-a8027816.html).

Kachel, Sven, Melanie C. Steffens, and Claudia Niedlich. 2016. “Traditional Masculinity and Femininity: Validation of a New Scale Assessing Gender Roles.” Frontiers in Psychology 7:361–19.

Kaplan, Hillard, Kim Hill, Jane Lancaster, and A M. Hurtado. 2000. “A Theory of Human Life History Evolution: Diet, Intelligence, and Longevity.” Evolutionary Anthropology 9(4):156–85.

Khan, Shehab. 2016. “Writer Who Coined the Term ‘Herbivore Men’ to Explain Japan’s Problem with Sex Speaks Out on Term’s Misuse.” Independent. Retrieved April 7, 2018 (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/japan-sex-problem-maki-fukasawa-a7347456.html).

Kimmel, Michael. 2008. Guyland: the Perilous World Where Boys Become Men. 1st ed. London, New York: Harper Collins.

Klein, Betsy. 2019. “Fast Food Once Again Served at White House Sports Event with Trump.” CNN. Retrieved April 26, 2019 (https://www.cnn.com/2019/03/04/politics/trump-fast-food-white-house/index.html).

Leroy, Frédéric and Istvan Praet. 2015. “Meat Traditions. the Co-Evolution of Humans and Meat.” Appetite 90©:200–211.

Lim, Louisa. 2009. “In Japan, ‘Herbivore’ Boys Subvert Ideas of Manhood.” NPR. Retrieved April 7, 2018 (https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=120696816).

Lockie, Stewart and Lyn Collie. 1999. “‘Feed the Man Meat.’” Pp. 255–73 in Restructuring Global and Regional Agricultures, Gendered food and theories of consumption, edited by D. Burch, J. Goss, and G. Lawrence. Aldershot, Hants, England, Brookfield, United States.

McGrane, Sally. 2013. “The Right-Wing Organic Farmers of Germany.” The New Yorker. Retrieved May 2, 2019 (https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-right-wing-organic-farmers-of-germany).

Millum, Joseph. 2018. Characteristics of Self-Identified Vegetarians in the United States, 2007-2010. Faunalytics.

Mooney, Kim M. and Erica Lorenz. 1997. “The Effects of Food and Gender on Interpersonal Perceptions.” Sex Roles 36:639–53.

Morioka, Masahiro. 2013. “A Phenomenological Study of ‘Herbivore Men’ Masahiro Morioka.” The Review of Life Studies 4:1–20.

Mycek, Mari K. 2018. “Meatless Meals and Masculinity: How Veg Men Explain Their Plant-Based Diets.” Food and Foodways 89:1–24.

Nath, Jemál. 2011. “Gendered Fare?” Journal of Sociology 47(3):261–78.

Neill, Moran. 2009. “Japan’s “Herbivore Men” — Less Interested in Sex, Money.” CNN. Retrieved April 7, 2018 (http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/asiapcf/06/05/japan.herbivore.men/index.html).

Newcombe, Mark A., Mary B. McCarthy, James M. Cronin, and Sinéad N. McCarthy. 2012. “‘Eat Like a Man’: a Social Constructionist Analysis of the Role of Food in Men’s Lives.” Appetite 59(2):391–98.

Nikkhah, Roya. 2013. “Hitler’s Food Taster Speaks of Führer’s Vegetarian Diet.” The Telegraph. Retrieved May 2, 2019 (https://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/world-war-two/9859294/Hitlers-food-taster-speaks-of-Fuhrers-vegetarian-diet.html).

Otagaki, Yumi. 2009. “Japan’s “Herbivore” Men Shun Corporate Life, Sex.” Reuters. Retrieved April 7, 2018 (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-japan-herbivores/japans-herbivore-men-shun-corporate-life-sex-idUSTRE56Q0C220090727).

Oxford University Press. n.d. “Cuck.” Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved April 23, 2019 (https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/cuck).

P, Charlier, Weil R, Rainsard P, Poupon J, and Brisard J C. 2018. “The Remains of Adolf Hitler: a Biomedical Analysis and Definitive Identification.” European Journal of Internal Medicine 54:e10–e12.

Pearce, Lisa D. 2002. “Integrating Survey and Ethnographic Methods for Systematic Anomalous Case Analysis.” Sociological Methodology 32(2):103–32.

Reinhart, R J. 2019. “Snapshot: Few Americans Vegetarian or Vegan.” Gallup. Retrieved April 7, 2019 (https://news.gallup.com/poll/238328/snapshot-few-americans-vegetarian-vegan.aspx?g_source=link_NEWSV9&g_medium=NEWSFEED&g_campaign=item_&g_content=Snapshot%3a%2520Few%2520Americans%2520Vegetarian%2520or%2520Vegan).

Roos, Gun, Ritva Prättälä, and Katriina Koski. 2001. “Men, Masculinity and Food.” Appetite 37(1):47–56.

Rothgerber, Hank. 2012. “Real Men Don’t Eat (Vegetable) Quiche: Masculinity and the Justification of Meat Consumption.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity 14(4):363–75.

Rothman, Lauren. 2018. “Men Are Embarrassed to Order Vegetarian Food, British Study Finds.” VICE.

Ruby, Matthew B. and Steven J. Heine. 2011. “Meat, Morals, and Masculinity.” Appetite 56(2):447–50.

Schösler, Hanna, Joop de Boer, Jan J. Boersema, and Harry Aiking. 2015. “Meat and Masculinity Among Young Chinese, Turkish and Dutch Adults in the Netherlands.” Appetite 89:152–59.

Sell, Aaron, Aaron W. Lukazsweski, and Michael Townsley. 2017. “Cues of Upper Body Strength Account for Most of the Variance in Men’s Bodily Attractiveness.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284(1869):20171819–8.

Shackelford, Todd K., David P. Schmitt, and David M. Buss. 2005. “Universal Dimensions of Human Mate Preferences.” Personality and Individual Differences 39(2):447–58.

Simpson, Mark. 2002. “Meet the Metrosexual.” Salon. Retrieved April 26, 2019 (salon.com/2002/07/22/metrosexual).

Sobal, Jeffery. 2006. “Men, Meat, and Marriage.” Food and Foodways 13(1-2):135–58.

Stenberg, Alyssa. 2017. “Vegan Men Speak Out!” ProQuest, Fullerton, California.

Thomas, Margaret A. 2015. “Are Vegans the Same as Vegetarians? the Effect of Diet on Perceptions of Masculinity.” Appetite 97:79–86.

Ulaby, Neda. 2014. “For These Vegans, Masculinity Means Protecting the Planet.” All Things Considered 5:59(1):1–3.

Vandello, Joseph A. and Jennifer K. Bosson. 2013. “Hard Won and Easily Lost: a Review and Synthesis of Theory and Research on Precarious Manhood.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity 14(2):101–13.

Vinik, Danny. 2019. “A $60 Million Pork Kickback?” Politico 1–5. Retrieved April 26, 2019 (politico.com/agenda/story/2015/08/a-60-million-pork-kickback-000210).

Woodvine, Amanda. 2009. “The Protein Myth.” VivaHealth. Retrieved April 25, 2019 (https://www.vivahealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/Protein-vegetarian-vegan.pdf).

Yang, Alan. 2011. “Go Big or Go Home.” Parks and Recreation. edited by D. Holland. NBC.

Zink, Katherine D. and Daniel E. Lieberman. 2016. “Impact of Meat and Lower Palaeolithic Food Processing Techniques on Chewing in Humans.” Nature 531(7595):500–503.

2019a. “Hall of Famers.” Meat Industry Hall of Fame.

2019b. “Urban Dictionary: Soy Boy.” Urban Dictionary 1–2. Retrieved April 21, 2019b (https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Soy Boy&page=5).

Appendices

Appendix A: Tables

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics of Survey Respondents

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | N = | % | N = | % |

| White | 10 | 83.3 | 11 | 73.3 |

| Latino | 1 | 8.3 | 2 | 13.3 |

| Asian | 1 | 8.3 | 1 | 6.7 |

| Multiracial | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.7 |

| Sexuality | ||||

| Hetero | 9 | 75 | 9 | 56.3 |

| Bi | 3 | 25 | 7 | 43.8 |

| Education | ||||

| Some high school | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.3 |

| High school grad | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Some college | 4 | 33.3 | 5 | 31.3 |

| College grad | 3 | 25 | 4 | 25 |

| Grad/Professional | 4 | 33.3 | 6 | 37.5 |

| Income | ||||

| ≤$24,999 | 1 | 8.3 | 2 | 12.5 |

| $25,000 – $49,999 | 1 | 8.3 | 4 | 25 |

| $50,000 – $74,999 | 1 | 8.3 | 5 | 31.3 |

| $75,000 – $99,999 | 5 | 41.7 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥$100,000 | 4 | 33.3 | 5 | 31.3 |

| Total | 12 | 100 | 16 | 100 |

Table 2: Gender Expression and Preferences

| Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M = | M = | p | |

| Relationship Length (years) | 3.3 | 2.4* | 0.345 |

| Self-Reported Gender Expression | 2.44 | 3.71 | < 0.01 |

| Gender Preferences | |||

| Personal Expression | 3.1 | 3.34 | 0.159 |

| Ideal Partner Expression | 2.96 | 2.83 | 0.264 |

| Aggregate | 2.97 | 3.05 | 0.345 |

Appendix B: Copy of Survey

Relationships with Veg* Partners

Thank you for your interest in this survey. This survey will be used to explore the dynamics of romantic relationships with those who identify as vegan or vegetarian.

- Duration: Approximately 2 – 3 minutes

- Subjects will remain anonymous unless you provide confidential contact information at the end of the survey for interviewing purposes.

All questions, unless otherwise specified, are on a scale of 5

Are you currently or have you ever been in a relationship with a person who identifies as a vegetarian or vegan for at least one month?

- Yes

- No

Approximately how long did this relationship last? If the relationship is ongoing, please enter today’s date.

- Approximate Start Date

- Month, day, year

- Approximate End Date

- Month, day, year

Which of the following do you most identify with?

- Male

- Female

- if true, then skip to “Female”*

Male

Personality

I would consider myself an…

- Unemotional person

- Extremely emotional person

When solving problems, making decisions, and forming arguments, I tend to be…

- mostly logical

- mostly emotional/intuitional

How important are the following items to you?

A high paying job

- Not important

- Very important

Working out

- Not important

- Very important

Eating a healthy, balanced diet

- Not important

- Very important

Your Ideal Partner

My ideal partner would be…

- a person with little-to-no-emotion

- a very emotional person

When solving problems, making decisions, and forming arguments, they would be…

- very logical

- very emotional/intuitional

What is the minimum level of education you’d accept in your partner?

-

Some high school

- High school graduate

- Some college

- College graduate

- Graduate/Professional Degree

How important should the following characteristics be for your ideal partner?

Maintaining a slim figure

- Not important

- Very important

Having the same amount of ambition as yourself

- Not important

- Very important

Having an equivalent level of education

- Not important

- Very important

Eating a healthy, balanced diet

- Not important

- Very important

Miscellaneous

A normal job for a woman is a nurse.

- Strongly disagree

- Strongly agree

Select how you would want your ideal partner to behave or identify

- Very masculine

- Very feminine

Skip to “Background Information.”

Female

Personality

I would consider myself an…

- Unemotional person

- Extremely emotional person

When solving problems, making decisions, and forming arguments, I tend to be…

- mostly logical

- mostly emotional/intuitional

How important are the following items to you?

A high paying job

- Not important

- Very important

Maintaining a slim figure

- Not important

- Very important

Eating a healthy, balanced diet

- Not important

- Very important

Your Ideal Partner

My ideal partner would be…

- a person with little-to-no emotion

- a very emotional person

When solving problems, making decisions, and forming arguments, they would be…

- very logical

- very emotional/intuitional

What is the minimum level of education you’d accept in your partner?

- Some high school

- High school graduate

- Some college

- College graduate

- Graduate/Professional Degree

How important should the following characteristics be for your ideal partner?

A high paying job

- Not important

- Very important

Working out

- Not important

- Very important

Being the same race as yourself

- Not important

- Very important

Eating a healthy, balanced diet

- Not important

- Very important

Miscellaneous

In general, a normal job for a man is a firefighter

- Strongly disagree

- Strongly agree

Select how you would want your ideal partner to behave or identify.

- Very masculine

- Very feminine

Background Information

How old are you?

- User integer response

How would you describe your behavior in general?

- Very masculine

- Very feminine

Do you consider yourself to be:

- Heterosexual (straight)

- Bisexual

- Homosexual (gay/lesbian)

- Other (user-inputted string response)

Which of the following best describes your highest level of school completion?

- Some high school

- High school graduate

- Some college

- College graduate

- Graduate school/Professional degree

What was your family’s approximate average annual household income growing up? (0 – 18 years old)

- $24,999 or lower

- $25,000 – $49,999

- $50,000 – $74,999

- $75,000 – $99,999

- $100,000 and above

Which racial category do you primarily identify with?

- White

- Black

- Latino

- Asian

- Multiracial

- Prefer not to say

*Note: Male and female indicators are not present on the actual survey to prevent bias.